Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

HISTORY

The Life of Miles Davis

The famous jazz trumpeter and composer became one of the most influential and acclaimed artists in the history of jazz music.

By Will Street

Jul. 25, 2019, 11:30 AM

RELATED

Introduction

One of jazz’s most acclaimed musicians of all time, Miles Davis was at the forefront of many stylistic jazz movements throughout a five-decade long career. Forming bands, composing music and adopting a variety of instruments, most famously the trumpet, Miles Davis produced a number of world-defining compositions and forever changed jazz music.

Born in Alton, Illinois, in 1926, Davis’ career spanned a period of great change in jazz music and what has come to be considered the “Golden Age” of jazz. It was a time when technological innovations and new movements spread into the streams of the genre, and the record sales of any successful musician could sky-rocket. In the documentations below, I explore the life of Miles Davis in more detail.

Early Life

Miles Davis was born on the 26th May 1926 to his parents Cleota Davis and Miles Davis Junior in Alton, Illinois. His father, Miles Davis Jr., was a prosperous dental surgeon. He also had two siblings: an older sister called Dorothy (born 1925) and a younger brother called Vernon (born 1929). Before long, in 1927, the family moved from Alton to East St. Louis in Illinois.

There Davis attended school and initially enjoyed listening to music such as blues, big bands and gospel. Although his father could be distant at times, owing to the Great Depression, which at times could cause him to work six days a week, before long he picked up the trumpet after a friend of his father, John Eubanks, had given one to him as a gift in 1935.

After playing with several bands in the St.Louis area during his adolescence, Davis decided to take his father’s advice and apply to study at Institute of Musical Art, now known as the Juilliard School. After passing the audition, he enrolled in the institution in 1944.

Early Career

Once at the Institute of Musical Art, Davis skipped many lessons, instead focusing on developing his craft through jam sessions with jazz masters that included Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Davis would perform at jazz venues in Harlem, and was so eager to take up performing full time that in mid-1945, after three semesters as a student, he dropped out of the Institute of Musical Art. Davis later criticized the school for focusing too much on white and European streams of music, however praised the institution for teaching him musical theory and improving his trumpet technique.

Once a free jazz musician, Davis performed in a range of New York jazz venues, along with replacing Dizzy Gillespie in Charlie Parker’s quintet in 1945. In the years between 1945-1948 Davis and Charlie Parker recorded often together.

In the summer of 1948, Davis took his career a step further, forming a nonet that included renowned jazz musicians Gerry Mulligan, J.J. Johnson, Kenny Clarke and Lee Konitz. The music that followed came to be known as Cool Jazz.

Playing alongside his nonet, the arrangements went against the flexible, improvisatory nature of the Bepop that he had recorded with Charlie Parker, instead producing thickly textured orchestral sounds. The group only lasted for a brief period yet produced a dozen tracks that were released as singles from 1949-1950, in the process changing the course of jazz music and paving the way for the West Coast styles of the 1950s. The dozen singles were later collected in the album Birth of the Cool (1957).

Modal Jazz

The early 1950s saw Davis afflicted by drug addiction, which left his musical production somewhat of a secondary entity and hindered his career. However, he was still able to produce some albums that rank amongst his best, joining forces with jazz notables including Sonny Rollins, Milt Jackson and Thelonius Monk. 1954 would prove the year he finally overcame his drug addiction, leaving Davis to start a two-decade period in which his music flourished, and he came to be considered the most innovative musician in jazz.

The theme of the period was modal jazz. Having formed bands in the early 1950s and released a string on much acclaimed albums, featuring the legendary saxophonist, John Coltrane, for one and the pianist Bill Evans, Davis capped the period off with the release of Kind of Blue in 1959, which is arguably the most celebrated album in the history of jazz.

Described as “modal” jazz, Davis adopted a style in which the improvisations were centred on sparse chords and non-standard scales. It went in direct contrast to the complex, frequently-changing chords of music previously released. As a mellow and relaxed ensemble, the music lent itself to solos that were focused on the melody itself, which was considered highly innovative in its day. The serenity of the sounds and accessibility of the music ensured it was highly popular with jazz fans.

Free Jazz and Fusion

Turning down the innovation a notch in the 1960s, instead deploying more subtle innovations and influxes, Davis would go on to form a new small band in 1962 with bassist Ron Carter, pianist Herbie Hancock and teenage drummer Tony Williams. They would be joined by saxophonist Wayne Shorter in 1964.

The sounds were characterised as light and free, and experimented with polyrhythm and polytonality that formed into a movement termed “free jazz”. Daring to go off the grid with their chords and notes, the band left behind a string of much acclaimed and influential albums in the mid-1960s.

As the clock moved into the late 1960s, Davis embarked on a journey away from free jazz towards a style that would win over news fans and start a new course of jazz music. The style he picked up was jazz fusion, something that took advantage of new technological innovations such as the electric guitar and, accordingly, produced sounds never heard before. What is generally considered as the seminal album of the movement, In a Silent Way (1969), came from Davis and his band themselves and experimented with electronic instruments. However, this newfound influx of electronic instruments was leading Davis down a path in such a direction that jazz purists consider the album to be Davis’ last true work of jazz.

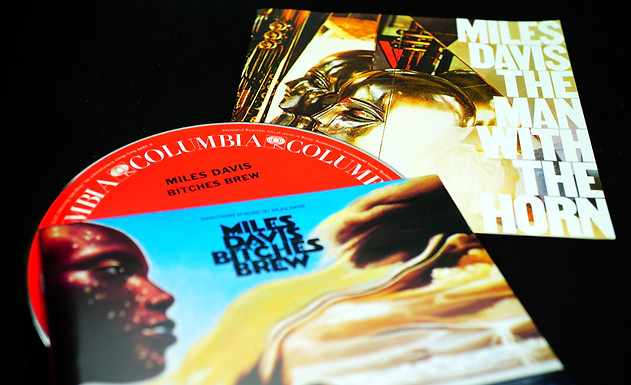

Winning over news but leaving some disenchanted others left behind, Davis fully adopted electronic instruments and the studio effects of rock music, releasing the album Bitches Brew in 1969. With a wider audience and more central position within music in general, Davis continued exploring this rhythmic and textured movement until he was involved in a car crash in 1972, which curtailed his activities.

Later Years

Following Miles Davis’ involvement in a car accident in 1972, he then retired from his music from 1975 to 1980. In 1980, he made a comeback and continued to focus predominately on jazz-rock dance music. During the period, Davis also picked several Grammy awards for albums such as We Want Miles (1982), Tutu (1986) and Aura (1989).

His influence on wider societal events would also be noticeable. In 1985, he joined the Artists United Against Apartheid and recorded the protest song “Sun City” against the ongoing apartheid laws in South Africa. Involving himself more in mainstream music, he also appeared on the instrumental for “Don’t Stop Me Now” by Toto in 1986.

During his later years, Davis would work on soundtracks for multiple films and even have cameo appearances as different musicians in others. In 1990 he was awarded with the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, saluting his extraordinary career.

A notable moment of reminiscence over former jazz times was the Montreux Jazz Festival, in 1991, where Davis joined an orchestra conducted by Quincy Jones and performed some classic Gil Evans arrangements from the 1950s. However, less than three months later, much to the dismay of the world, Davis passed away at the age of 65. A funeral service was held in St. Peter’s Lutheran Church on Lexington Avenue on the 5th October 1991 and he was later buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, alongside one of his trumpets. His loving companion would accompany him to the end.

Conclusion

A musician who was at the centre and influenced many new jazz movements throughout his lifetime, Miles Davis is extolled as one of the greatest jazz musicians of all time. Recording iconic jazz tracks in the 1950s and 60s and keeping jazz relevant to a mainstream audience during the later stages of his career, Davis has a left behind a string of compositions that still sound as beautiful today. Someone who was always keen to innovate and was a creative as he strove to be throughout his career, Miles Davis undeniably warrants his place in the music hall of fame.